While the crowd gathered at the Mid-Century Modern LIRR train station at Douglaston, I looked over at my Jane’s Walk co-tour guides, good friends and fellow architects, the Brothers Dadras—Robert and Victor—and I could see their jaws drop too.

Jane’s Walkers were arriving in droves—coming from all over the City to see Douglas Manor’s historic Arts & Crafts houses.

Douglaston’s Mid-century Modern station house by local architect Gordon Lorimer, marked the starting point for our Jane’s Walk 2018. The station was built in 1962. Lorimer said his design intentionally echoed the Tudor style of “The Village” storefronts nearby. Battered and frayed, it will undergo a rehab—not a “restoration”—by the MTA later this year.

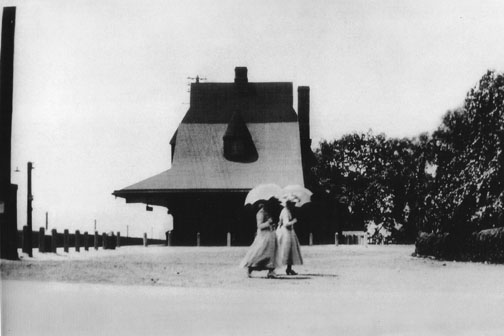

Lorimer’s station house replaced this boldly masculine 1888 Queen Anne station house with an apartment above for the station master, that by 1962 was deemed “obsolete.” The building was replete with Tudor style beams, pebble dash stucco panels, multi-light sash, a stylized rounded turret, and exaggerated brackets holding up an overhang to protect passengers from the weather.

Just before the kick off time of 1 pm, the crowd had surged in a matter of minutes from 30 to 40 to 60—and we were expecting 30, tops—filling the café tables at our LIRR stop area that we all fondly call “The Village” while they waited for Jane’s Walk 2018 to begin.

We were off to see just a smattering of the largest collection of Arts & Crafts style houses in New York City, all a few minutes walk away within the borders of Douglas Manor in the Douglaston Historic District.

Victor, Robert and I had led Jane’s Walks in Douglaston together twice before, but never had there been such a crowd.

In New York, Jane’s Walk is sponsored by the Municipal Arts Society, in honor of Jane Jacobs, a dragon slayer of a woman who first took on the mighty Master Builder Robert Moses in the 1950s successfully derailing his plan to build a highway through the middle of Washington Square Park.

Jacobs, untrained in city planning, wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a critique of city planning and urban renewal that was nothing short of revolutionary.

Her influence was so great that she changed the way that every urban designer, architect and city planner today thinks about cities.

This map shows the subdivision of the original Douglas estate, a mile long peninsula jutting into Little Neck Bay. The construction of the railroad tunnels under the East River and Penn Station in 1910 made daily commuting from Douglas Manor to Manhattan possible. Such was the demand that over a million dollars worth of lots were sold on site during a March snowstorm in 1906. Today there are 600 single-family homes here, most built before 1930.

As a tribute to Jacobs (she died in 2006) Jane’s Walk happens simultaneously on the same May weekend each year in cities all over the world.

Urban enthusiasts of all stripes volunteer to lead walks to show perfect strangers why their particular neighborhood is special—and all Jane’s Walks are free and open to everyone.

This year, as a joint effort of the Douglaston Local Development Corporation and the Douglaston & Little Neck Historical Society, we decided to thematically focus our local Jane’s Walk on Douglas Manor’s great Arts & Crafts houses.

When good friends and neighbors Don and Leela Fiorino heard of our plan, they generously offered to host an end of the walk Reception at their Arts & Crafts gem, a 1911 gambrel roofed rose covered cottage, with a richly outfitted interior in oak, that rivals any that Arts & Crafts master Gustav Stickley might have designed.

With Robert holding his “pig snout” amplifier for me to speak, and Victor “herding cats" in the rear, we embarked on our journey.

Victor introduced the group to the LDC’s ongoing efforts to revitalize the Station area. The railroad connection to Manhattan made the development of Douglas Manor possible.

We stopped to see three Stickley houses along the way—two of which are straight out of The Craftsman magazine plans that Stickley published—and another dozen houses that exemplify the Arts & Crafts tradition in America.

The 600 houses of Douglas Manor are arrayed along its romantically winding streets with a range of eclectic styles typical of the early 20th century. Many of the house designs exemplify the tenets of the Arts & Crafts ethos of the time, that a true home requires:

BEAUTY

SIMPLICITY

UTILITY

ORGANIC HARMONY

The Manor’s Arts & Crafts houses do just that.

140 Prospect Avenue: This simple gray stucco house with dark brown trim was recently restored, opening up the second story porch that had been enclosed. The play of solid and void is typical of Stickley’s house designs. This is House No. 85 from The Craftsman magazine, 1910. The rendering from 1910 and what was built at Douglas Manor are identical.

Typical of Stickley’s designs, the first floor plan of No. 85 reveals a generous but sequestered (typical of the time) kitchen with many built-ins. There are also built-ins for books with windows above, a built-in “Seat” at the Living Room, and built-in double china closets with a large sideboard at the Dining Room, still extant. A door from the Dining Room leads to the covered porch.

Although a modest house, the second floor of No. 85 also includes an outdoor balcony and a sewing room as amenities, with a shared bathroom for the three bedrooms. The “state-of-the-art” bathroom boasted a shower with a full body spray feature. Note how the bedrooms “pinwheel” around the hallway—very Frank Lloyd Wright.

A Craftsman-style fountain: At the side of 140 Prospect is a small garden. A recent owner added this simple but attractive fountain (not yet turned on) on axis with the open porch at the first floor. Passers-by get a nice glimpse of it and get to hear it, too.

For Plan No. 85, Stickley suggested furniture, including this simple chair and table.

Many of the houses are either overtly Arts & Crafts in style, or ornamented outside or inside with typical Arts & Crafts features. Arts & Crafts architecture is among my favorites, and I’ve not only renovated and restored some of the Manor’s finest specimens, I also designed an entirely new house in the District in the Arts & Crafts tradition that remains one of my favorite projects.

225 Hillside Avenue: Arts & Crafts style? Yes—but this yellow stucco house with white trim might also be described as a “Four Square,” which it is. It is nicely embellished with an inviting wraparound porch with a one-story Queen Anne-esque circular tower at one end. The rounded porch adds asymmetry to what is otherwise a perfectly symmetrical composition.

The railing on the porch shows a Classical influence, but like many Arts & Crafts style houses, the design has been simplified to basic geometric shapes, and in the process, transformed.

Originally, the trim on this house would’ve been painted a dark color, likely green or brown with gray or beige stucco. Shutters and window sashes may have been a different but complementary color, to add another layer of richness to the simple composition.

Jane’s Walk offered a chance to explore exactly what is meant by “Arts & Crafts” and what it is that makes a house an Arts & Crafts style house to begin with.

Our Jane’s Walkers had a lively discussion, and lots of questions along the way about the Arts & Crafts movement, New York City Landmark rules, and of course, “Arts & Crafts“ style. This is a tricky topic!

For the real answer is that there is no “Arts & Crafts” style.

The movement started in England in the mid 19th century with the rise of industrialism and in opposition to it, as a way to cultivate the handcrafted, and influenced everything from architecture to print making to furniture design to textile and graphic design.

Here in the States, the Arts & Crafts movement arrived a bit later, and morphed away from its Socialist edge the in England, to more of a middle class lifestyle that favored the handcrafted over the machined, with a fantasized version of family life and domestic bliss thrown into the mix.

The Arts & Crafts style and its ornament were a perfect match for places like Douglas Manor where the planned garden suburb reached by rail offered a green alternative to the increasingly mechanized and frenetic neighborhoods of Manhattan, but remained easily connected to it.

During the early 1900s, Douglas Manor was promoted for its natural assets and healthy liifestyle—the commonly owned shoreline perfect for strolls and picnics, with tennis, swimming, sailing, and golf all easily accessible—a mere half hour rail ride from mid-town Manhattan’s newly opened Pennsylvania Station.

104 Hollywood Avenue: Built during the pre-auto horse and buggy era, the Manor featured some grand homes like this one, as well as more modest ones to appeal to a range of the middle class.

This eclectic Arts & Crafts style house combines features like oversized fluted Classical columns with a gambrel roof and an open “piazza” that wrapped the house, and culminated with a covered porch facing west to capture views of the nearby Long Island Sound

By the turn of the century, even the wealthiest Manhattan neighborhoods were subject to commercial incursions because of a lack of zoning. Zoning didn’t begin in New York City until 1916. In 1906, the developers of Douglas Manor ensured that its borders were protected, using deed restrictions to create a community of freestanding single family houses, which communally shared and maintained a mile-long waterfront facing the Long Island Sound.

Gustav Stickley

A mid-Westerner who was the son of German immigrants, Gustav Stickley started life as a farmer. By 1900, he was publishing a magazine and owned a multi-story building in Manhattan where his offices were located with a ground floor showroom to sell his work.

He became the leading American proponent of the Arts & Crafts movement, and promoted the style with his magazine called The Craftsman, which featured the design work of his staff of architects and designers, who, along with himself, created house plans and furniture designs.

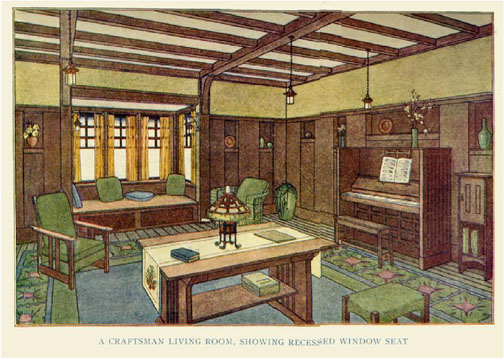

Stickley lavishly illustrated his magazine with color plates, showcasing interiors that had a careful balance of stained wood trim, his trademark built-ins—often oak—with contrasting plaster painted warm, earthy colors.

The magazine lasted from 1901 to 1916, when Stickley went bankrupt. The movement in America had run its course by the start of the 1920s.

Today, Stickley’s furniture is collectible and his houses and their offspring—they were widely imitated—are still revered by a certain enthusiastic few.

122 Arleigh Road: This 1909 Stickley No. 70 house from The Craftsman magazine shows the influence of Japanese architecture (also a fascination of Frank Lloyd Wright’s) with a long broad sloping roof, and the beautifully detailed entry porch.

This rendering of Plan No. 70 shows the house built at 122 Arleigh in an idealized setting of open countryside. Originally the multiple layers of shingles, board and batten and clapboard used for the exterior cladding would have been emphasized and highlighted in different colors instead of the monotones chosen today.

The first floor plan reveals a much more expansive—and expensive house—than Plan No. 85, with a 20 by 20 foot Living Room, three oversized fireplaces with decorative tile work, including one at the Kitchen, a powder room, and a “Billiard Room,” all interconnected by wide door openings, a predecessor to today’s “open concept plan.”

A 40-foot long covered porch faces west, capturing distant views of the Sound a block away.

Plan No. 70 is equally generous at the second floor with four bedrooms, an oversized 12’-0” by 15’6” Sewing Room (which could be a fifth bedroom), and a Servant’s Room. A huge “Balcony” over the covered porch below faces west. But there is only one bathroom.

Stickley designed built-ins for Plan No. 70 at the Dining Room, shown in this illustration. Readers could order plans from The Craftsman magazine, and then hire a local contractor to build the house.

The craze for all things Japanese triggered when America’s Commodore Matthew Perry opened trade to Japan in the mid 19th century, continued unabated into the early 20th. Here, the simple but elegant forms of Japanese architecture find their way into the timber details at the front entry portico.

The Arts & Crafts movement here embodied many disparate eclectic styles of the time including the unlikely Colonial Revival (no one dares describe a Colonial Revival house as Arts & Crafts), so popular at the turn of the last century and a style which endures to this day.

In Douglas Manor there are many early 20th century Colonial Revival style houses that follow the tenets of that style exactly at the exterior. However, once one steps inside, there are often elements that speak to the Arts & Crafts movement so popular at the time.

Classic Colonial Revival: Even the most faithful Colonial Revival exterior may belie Arts & Crafts touches at the interior, including hand made decorative tile work, art glass light fixtures and other handcrafted features that were all the rage during the early 20th century.

This could be in the form of hand made Grueby or Batchelder tile work around the fireplace openings, artisan crafted light fixtures with leaded and opalescent glass, or sometimes the mix of overtly Classical detailing with Arts & Crafts references, like leaded glass windows—and nothing Colonial Revival about it.

28 Shore Road: Jane’s Walkers gather outside a late Queen Anne (1909) designed by architect Carl P. Johnson, originally with a bell shaped cap over the 3-story tower, now missing. The interior is outfitted with golden oak woodwork and wainscoting and handmade Arts & Crafts tiles at the Dining Room.

A few years after completion, the owners added a multi-sided sunroom at the south side with leaded glass windows and capped by a squirrel weathervane. The gray squirrel was a favorite domestic pet of the late 19th century.

At the Manor, the Colonial Revival houses we passed on our walk tended to be of the gambrel roofed variety, and so subject to more overt expressions of the Arts & Crafts style at the exterior.

37 Circle Road: Gambrel roofed Colonial, or Arts & Crafts cottage? Bracketed by a pink flowering dogwood and a mature beech tree, this house adjacent to No. 85, sports window shutters with a unique cutout typical of the whimsical details favored by Arts & Crafts era designers.

Our Jane’s Walk was a strenuous walk that lasted almost two hours up and down some of the hilliest streets of the Manor. But even an elderly guest with a walker was undeterred and hung in there until the reception at the Fiorinos'.

Herewith, some highlights of our tour:

309 Hillside Avenue: This “Medieval Spanish Baroque Revival” mansion was designed and built in 1916 by Elbert McGran Jackson, a Southerner by birth and an architect by training. A colonnade of Moroccan-inspired leaded glass windows at the second floor is visible. I restored this house and designed the garden for the current owner 20 years ago. It is among my favorite projects.

Jackson first built a two-story high studio for painting in 1916, and added multiple additions to the copper roofed house over the next 20 years. The interior of the house is decorated with his handiwork as well, including hand painted beams, evoking a Middle Eastern casbah, complete with a backyard grotto.

A steep cobblestone driveway leads to a Model T sized garage at Jackson’s mansion, known locally as “The Alhambra.” McGran’s original painting studio is to the left of the garage.

An arched stucco wall with a wooden gate at the sidewalk promises mysteries beyond. Once inside the gate a curving path leads to a front garden filled with spring flowering trees and roses in the summer, leading up to a raised terrace at the front door.

329 Forest Road: Jane’s Walkers fill the brick paved forecourt to artist Trygve Hammer’s house and studio. Hammer was a Norwegian painter and sculptor who designed the bas-reliefs of the now demolished Bonwit Teller building (site of Trump Tower) in Manhattan, as well as other sculptures throughout New York City and the region.

Hammer first built a studio here for himself in 1916, and then added on to it to make this his full-time home. The hand carved bargeboards and other decoration at the gable peak are his handiwork. He also fashioned the leaded glass windows at the kitchen, to the right

Hammer’s house evokes the traditional houses of his native homeland—think snow and skis—and is encircled by ten one hundred foot tall Norway spruces that are the favored haunt of owls.

My wife and I lived next door to this house until recently. Every morning was a delight to wake up and look upon Trygve’s roost from our perch slightly uphill, especially in the snow when the dark stained vertical boards and turquoise trim provided high contrast. Locals call this house “The Chalet.”

202 Shore Road Before & After: This house facing the Long Island Sound was designed by Werner & Windolph in 1919 in the Arts & Crafts style. Five different additions were built over the years, and the original all stucco house was covered with aluminum siding in the 1950s, obliterating what it once looked like.

Two world famous artists have called 202 Shore Road home, the German artist George Grosz, and the famed Chilean pianist, Claudio Arrau.

Before renovation, aluminum siding still covered every surface of the original stucco house. I renovated and re-imagined the house inside and out for the current owners. Arrau’s piano room was demolished, opening up 180 degree views of the waterfront the room had blocked, and allowing the construction of a new pergola to replace the long missing historic one.

To break up the massing, the upper story was covered in cedar shingles left to weather gray, the lower story stuccoed in beige, and the windows and trim painted dark green—a true Arts & Crafts composition.

111 Hollywood Avenue: Another Stickley house (1919) custom built at the time for an attorney, this simple elegant house with a hipped roof and broad eaves exemplifies the ethos of its designer, and marks the end of the Arts & Crafts era in America. Plans for this are archived at Columbia University’s Avery Library. Nearly two decades ago, I designed a lush English style garden around an existing swimming pool at the rear yard for the current owners.

By the time we were a few blocks away from the Fiorinos' our Jane’s Walk crowd had surged to 70. I called Lee to warn them. “Bring ‘em on!” she cheered enthusiastically, followed by a huge laugh. And so we did. Our Jane’s Walkers, tired, hungry and thirsty, were greeted by a beatific Lee who revels in having parties, even for strangers!

Fiorina Residence: Don and Leelas' stucco and shingled gambrel roofed house designed by architect George Chichester in 1911 exemplifies many features of the Arts & Crafts style.

The house was restored several years ago. New cedar shingles were installed and new colors were selected, including a bright orange front door, green trim and dark red sash at the windows. In a few weeks the roses will come out, flanking the first floor bay window, and encircling the screened porch at the rear.

I designed a new screen porch addition for Don & Leela, with a circular bluestone terrace and a “no grass garden” of perennials surrounding it. A favorite gathering space for relaxing, the garden and terrace complete the picture of early Twentieth century ideals of domesticity promoted by the Arts & Crafts movement

Our Jane's Walkers flowed in like a tidal wave, and then spread themselves through the garden and first floor of the house to kick back, relax and enjoy a feast of cheeses, fruit, Prosecco and wines donated by the Historical Society.

Our hosts encouraged them to take a house tour if they liked, and many were treated to the Fiorino’s spectacular third floor Shrine Room—they are both practicing Buddhists and travel to Nepal often—to see not only the room, but the views from the top floor.

A half moon window at one end frames views east over the Great Neck peninsula , and a window mid-attic facing north overlooks the treetops of the mile long Douglas Manor peninsula.

As one beatific Jane’s Walker commented upon returning to earth after visiting the Shrine Room—“Heavenly!